Ohio State alumnus Peter Precario looks back 50 years at Ohio State’s celebration of the first Earth Day with frustration assuaged by optimism.

He sees deregulation stifling environmental progress, and yet today’s passionate youth give him hope.

|

“Earth Day was a powerful political voice,” he says. “At the time, people said, ‘This is just a bunch of crazy kids where were rioting against the Vietnam War and are now demonstrating for the environment.’ Amazingly enough, it’s lasted for 50 years.”

On April 22, 1970, in a light rain, hundreds of Ohio State students, faculty and staff and community leaders gathered across campus to commemorate the first Earth Day at nearly two dozen events from dawn until past midnight.

At Browning Amphitheater, then-Gov. James A. Rhodes opened the day with a “Rite of Spring,” having declared the date as Earth Day in the state “in proud recognition of the constructive and intelligent perception of our concerned youth in this national challenge as evidenced by their active participation in 150 teach-ins on campuses the nation over.”

Among those concerned youth was Precario, who had completed his history degree in 1967 and remained on campus to obtain his law degree.

“One thing that came out of that first Earth Day,” he says, “was a sense of urgency.”

Indeed, within six years, Congress approved President Richard Nixon’s proposal to create the Environmental Protection Agency (December 1970) and passed the Clean Air Act (1970), Clean Water Act (1972), Endangered Species Act (1973) and Toxic Substances Control Act (1976).

National events also contributed to that urgency: The Cuyahoga River had repeatedly caught fire because it was so polluted with chemicals. Millions of gallons of oil spilled from an offshore rig fouled California beaches. And astronauts on the Apollo 11 mission to the moon photographed Earth from space, creating an awe-inspiring image that fortified concern for our planet.

Precario, as chair of the Legal Aspects and Civil Rights Committee for Ohio State’s first Earth Day celebration, put together a legal presentation for the university’s Earth Day events.

“It proved to be a daunting task, because prior to Earth Day there was no overall plan or law that really covered pollution events,” he remembers. Having developed a keen interest in water quality and environmental issues, Precario entered law school finding just one mentor: recently hired Professor Earl Murphy, a well-known expert in environmental law.

Precario recruited Murphy as the speaker for two of the day’s events: a historical perspective on the proposed environmental laws and a foray exploring what could be done in the future, the latter event featuring a Q&A that went far over its allotted time.

“These new environmental laws were kicked around for quite a while, particularly the Clean Water Act, which had its roots back in 1968 or 1969,” he says. “Because of the Cuyahoga River burning, the political pressure was so great that it finally got moving.

“There was a lot of debate about how these environmental laws were going to operate,” says Precario, who currently practices environmental law in Columbus, “because they cut across property law and other things that took a while to untangle — and in fact are still being untangled as we sit here today. But overall, it worked remarkably well.”

In 1970, he remembers, people were hopeful about these new developments. (Read the 1970 Makio yearbook page about Earth Day on campus.)

“There was a sense of optimism that things could be better — that pollution could be stopped, that we were setting standards,” he says.

Doug Brownfield also was on campus in 1970, having returned after four years of Naval service in the Vietnam Campaign.

|

“I returned very dedicated to finding ways to engrain myself in the strongest values I could find,” he says. “Back at the time of Earth Day, we were just planting the seeds of change.”

Brownfield, a communication student, was perusing the Lantern one day when he saw an ad for the student group ECO, Environmental Campus Organization, and decided to attend the first meeting. He and fellow student Carol Fischer set about establishing a recycling effort at Ohio State. From a meager start of one box of Lanterns delivered to a recycling facility, the two watched their efforts grow thanks to more awareness and participation. When eventually they made money instead of having to pay the recycler to take the paper, Keith Brooks, the chair of the communication program at the time, directed them to Richard Mall, then director of alumni affairs to talk about how their legacy could continue once both left campus.

“Dr. Mall’s conversation guided our program from the ‘idealistic’ concept to the ‘business aspects’ of having our program accepted and implemented by the university,” says Brownfield.

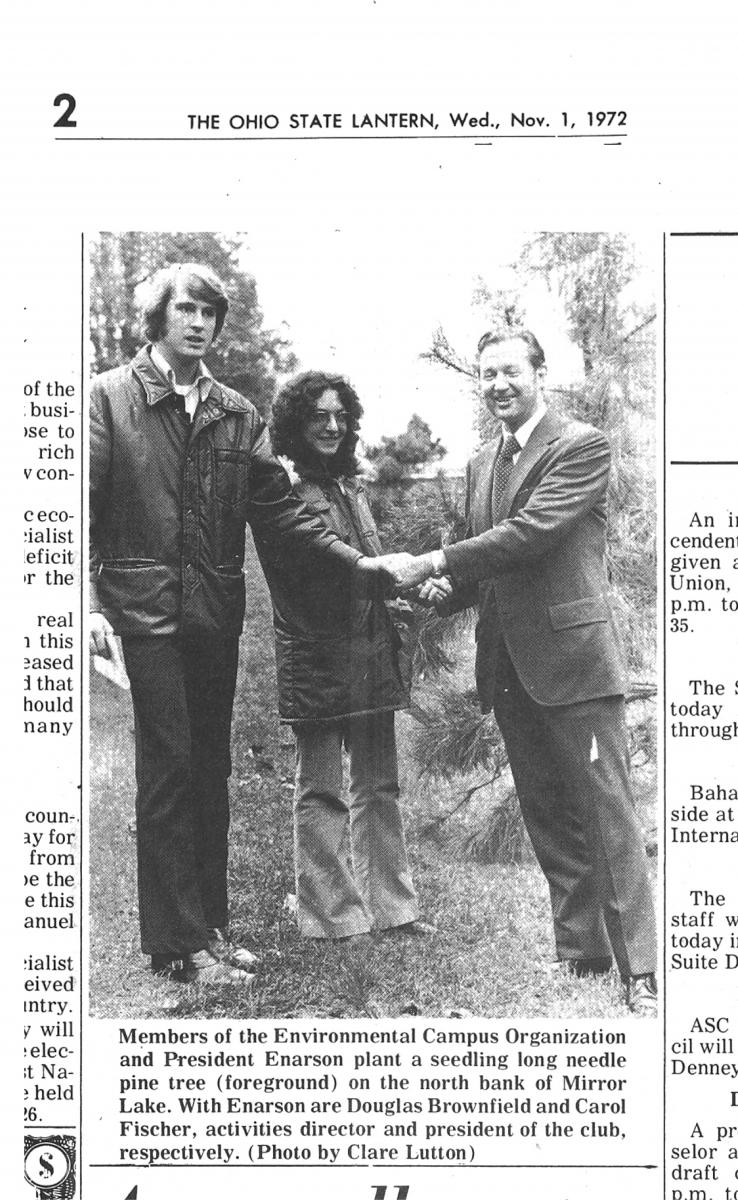

In 1972, Brownfield and Fisher attended a long-needle pine tree planting on the north bank of Mirror Lake with new university President Harold Enarson.

“He brought the tree from his property in Colorado — it was small and in a coffee can,” remembers Brownfield, who now assists in teaching an honors sociology course that links students with local businesses to address service-based goals. “His ceremonial words were, ‘We plant this tree not for its enjoyment today, but for the generations to follow.’”

That white pine still stands.

“Now as I hold class in the original university president’s house (Kuhn Honors and Scholars House at 220 W. 12th Ave.), I can see this high-as-the-sky tree,” Brownfield says, “the growth of the tree and the passage of decades reminding me of those words spoken almost 50 years ago.”

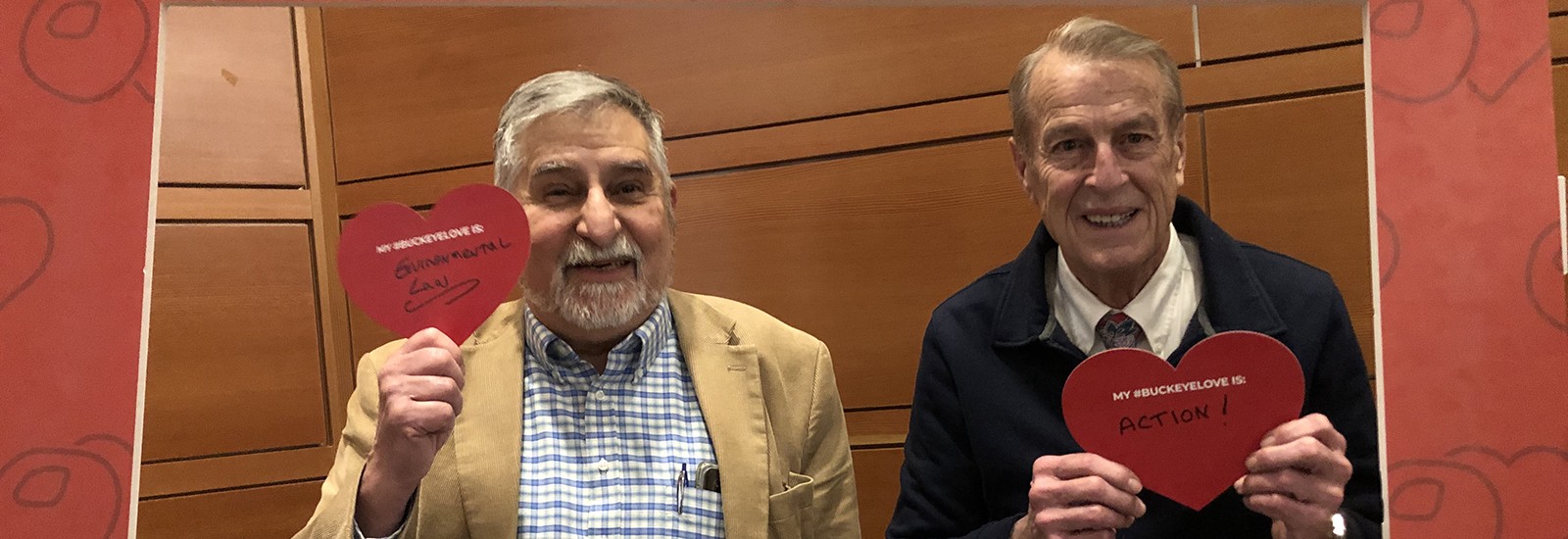

The influence of the first Earth Day still holds strong in the lives of Brownfield and Precario.

In addition to facilitating student and business community connections in the sociology course, Brownfield is now a project manager for community outreach at Lowe’s, coordinating the company’s involvement in projects such as the Schoenbaum Family Center and Crane Center for Early Childhood Research and Policy; the Universal Design Display House exhibit at the Farm Science Review; and Star House center for homeless youth.

Precario, after obtaining his law degree, worked for the newly created Ohio EPA and was appointed by then-Gov. Richard Celeste to the Environmental Board of Review (now the Environmental Review Appeals Commission), which hears appeals from cases that emanate from the state EPA. In addition to practicing environmental law, Precario now serves as executive director of the Midwest Biodiversity Institute, a research organization that surveys water quality using biological indicators.

Contemplating these 50 years since the first Earth Day, Brownfield and Precario can’t help but feel some frustration.

“The country’s leadership at the top is now deregulating all the things we fought for,” Brownfield laments.

“I find it ironic that now, after 50 years, that faith in science, that faith in regulations, that optimism that things can be solved is disappearing,” Precario says. “The changes made are being watered down quickly.”

And what about that sense of urgency Precario felt at the first Earth Day? The attorney watched as it waned over several decades, but he’s gaining hope.

“I think there is a newly forming sense of urgency, at least with the younger generation, the millennial crowd. It’s a bigger urgency; it’s a global urgency,” he says.

“The younger crowd, the college-age crowd that is emerging into this world, is worrying about the quality of the environment in the future and how we’re going to solve it. There was the same type of urgency in ’70s, when we knew there were people who denied we needed these laws even in face of the Cuyahoga River catching on fire,” he says, noting that the melting glaciers of Antarctica falling into the ocean provide that graphic backdrop today. “We’ve got to re-energize that urgency. The reason Earth Day is important now is the ability to energize the belief that something can be solved.”

He would remind the disheartened that there are, indeed, solutions — and solutions yet to be invented.

“It’s going to cause disruptions and economic changes and things that are uncomfortable, just like the clean air and clean water acts — but those things worked. We just need to bring out the desire to see them happen,” Precario says. “There is a lack of confidence that things can be improved, and lot of it is flat-out denial. You have to dedicate yourself to make the changes. Perhaps sacrifices come in, but you have to change and not be afraid of it.”